The Art of Invisible Code: The Trap the Best Programmers Fall Into

There is a fundamental paradox at the heart of modern computer science: a programmer’s value isn’t measured by the complexity of problems they can solve in a single line of code, but by the simplicity with which they make that line understandable to anyone else.

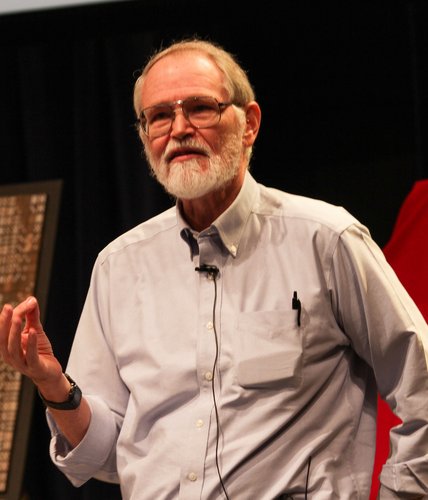

Brian Kernighan, one of the key contributors to Unix and co-author, along with Dennis Ritchie, of the celebrated book The C Programming Language, expressed it with brutal clarity in 1978:

— Brian W. Kernighan and P.J. Plauger, The Elements of Programming Style, 2nd edition (1978)

Photo: Ben Lowe, CC BY 2.0

This statement isn’t just an aphorism — it’s a thermodynamic law of software development. If we commit 100% of our cognitive faculties to “being clever” during the writing phase, we’re essentially taking on a debt we won’t be able to repay when, inevitably, that code breaks.

The Intelligence Trap

Let’s be clear: intelligence is enormously valuable at every stage of software development — in requirements analysis, architecture design, algorithm selection, implementation. Nobody is saying you should write trivial code or lower the bar. The point is different: when intelligence stops serving the project and starts serving our ego, it becomes a problem. Writing code that works but only you can decipher isn’t proof of intelligence — it’s proof of vanity.

And be careful: this does not mean that if a lazy colleague who hasn’t kept up with the times can’t read your code, you should lower yourself to their level. If someone on the team refuses to study language evolutions, modern patterns, or the tools the rest of the team has adopted, the problem is theirs — and the cost of that laziness falls on the entire team and the company. Code clarity assumes an adequate professional level from its readers.

That said, many developers fall into the “intelligence trap.” Writing nested functions, using multiple ternary operators, or exploiting the most obscure subtleties of a language gives immediate gratification: it makes us feel like modern wizards who dominate the machine. However, this is an exercise in vanity, not engineering.

In the software industry, code is almost never a solitary endeavor. It’s a living document that must survive the handoff between teams and generations of developers. When a “brilliant” programmer leaves the company (or simply changes projects), if their code was built on individual brilliance rather than shared standards, that code instantly becomes a financial liability.

The cost of software doesn’t lie in its creation, but in its maintenance. A successful software project spends 80-90% of its life in maintenance and evolution. Every line written today will be read, interpreted, and modified dozens of times in the months and years to come — often by people who didn’t write it. This means that every stylistic choice made during writing has a multiplier effect: clarity pays dividends for years, obscurity generates costs for years. In the era of AI Agents, this concept has become even more extreme. Today, a language model can generate hundreds of lines of code in seconds. Code “generation” has become a near-zero-cost commodity. The real value of the human engineer has shifted to the ability to validate, review, and integrate that code. If AI generates “clever” but obscure solutions, and the human can’t instantly decipher them to ensure maintainability, the advantage of initial speed is negated by future debugging costs.

Donald Knuth’s Lesson: Code as Literature

Donald Knuth, one of the greatest computer scientists in history, proposed in 1984 the concept of Literate Programming. The idea was revolutionary: stop thinking of code as something that instructs a computer, and start thinking of it as something that explains to a human being what we want the computer to do.

— Donald E. Knuth, "Literate Programming", The Computer Journal, Vol. 27, No. 2 (1984)

Photo: Alex Handy, CC BY-SA 2.0

The real value lies in the narrative. Code that “survives” is code that tells a clear story:

- The “What”: expressed through self-explanatory variable and function names.

- The “Why”: confined to comments, explaining architectural decisions and business constraints.

- The “How”: made so straightforward it’s boring.

“Boring” Code Is Modern Code

In software, we should aspire to the stability of “boring.”

However, be careful not to confuse “boring” code with “obsolete” code. Writing today the way we did ten years ago isn’t a sign of prudence, but of professional inertia. Being a “clear” programmer paradoxically requires more discipline and maturity than writing “clever” code.

The real value lies in knowing the new features of the language — like async/await, pattern matching, or new data structures — not to show off technique, but because these innovations were born precisely to eliminate visual noise and the old “tricks” needed in the past. An up-to-date programmer uses modernity to simplify: transforming ten lines of convoluted manual logic into a single declarative and expressive statement.

The 2 AM Test

If a new hire, in the middle of the night under the pressure of a system down, manages to fix a bug in a module written three years ago without causing side effects, that module is an engineering success. This is the true quality metric: the ability of code to be self-explanatory precisely when our cognitive capabilities are at their minimum.

Anatomy of Clarity vs. Anatomy of Cleverness

To understand where the value lies, let’s compare the two approaches:

- Variable names: “clever” code uses

temp,data,val. “Clear” code usesdaysSinceLastAccess,userToValidate,discountedProductList. - Functions: clever code creates “Swiss army knife” functions that do ten different things based on boolean parameters. Clear code follows the Single Responsibility Principle: one function, one job.

- Abstractions: the clever programmer abstracts everything immediately, creating complex class hierarchies “for the future.” The wise programmer follows the YAGNI principle (You Ain’t Gonna Need It): don’t add complexity until it’s strictly necessary.

Writing clear code isn’t an innate talent — it’s a skill built by studying SOLID principles, Design Patterns, and object-oriented design techniques. These tools exist precisely to give structure to clarity, transforming it from a vague aspiration into a concrete, repeatable practice. If you want to deepen these topics, you can start with a training course dedicated to patterns and object-oriented programming.

Hyrum’s Law and Corporate Responsibility

A fundamental reference is Hyrum’s Law, formulated by Hyrum Wright (Google):

“With a sufficient number of users of an API, it does not matter what you promise in the contract: all observable behaviors of your system will be depended on by somebody.”

— Hyrum Wright, hyrumslaw.com

This applies internally as well. If you write “clever” code that exploits an obscure side effect, someone will start depending on it. When you get moved to another project or change teams, nobody will dare touch that block of code for fear of breaking the entire ecosystem. This creates a “black box”: a portion of software that nobody understands, nobody maintains, and that slows down the entire company.

The value of an experienced programmer is seen in their ability to prevent the creation of these black boxes. They know that their presence on a module is fluid. The code must be able to walk on its own legs without the constant support of its original author.

Conclusion: True Intelligence Is Humble

Wanting to prove you’re the smartest person in the room is a limitation, not an achievement. Those who are truly aware of their capabilities care about the project’s success and the team’s growth, not their own image.

In a healthy ecosystem, if you’re the only one who can understand what you write, you’re not a pillar — you’re a single point of failure. This mentality transforms the programmer from collaborator to obstacle, as it prevents code review and saturates colleagues’ time with unnecessary explanations.

True genius isn’t in making simple things complex, but in making complex things simple. Kernighan wasn’t asking us to be less capable; he was asking us to use our capability to remove friction. The goal isn’t to show how good we are today, but how robust and scalable the system we leave behind is.

The next time you write a line of code, stop and ask yourself: “Am I trying to prove how good I am, or am I trying to help the project?” The answer will determine whether your work becomes a valuable asset or a technical nightmare.

As John F. Woods wrote in 1991:

“Always code as if the guy who ends up maintaining your code will be a violent psychopath who knows where you live.”

Write code as if the person who will maintain it were a violent psychopath who knows where you live. But, more importantly, write code knowing that person will most likely be you in six months. Be kind to yourself. Be boring. Be predictable. Be clear.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus